We've Come a Long Way

- 9/9/2016

- Ostomy

A look at ostomy pouching systems from a historical perspective

by Thom R. Nichols, Research Fellow: Biostatistics and Health Economics, Hollister Incorporated

This article first appeared in the Second Quarter 2016 issue of the Secure Start services eNewsletter.

In 2016, people with ostomies have a variety of pouching systems to choose from, but this certainly was not the case in the past. Let’s take a look at how the pouching system has evolved through the years.

The year is 1706 and historical records recount a battlefield wound resulting in a prolapsed colostomy. This instance, perhaps, is the first stoma ever recorded. In a mid-1700s surgical textbook there is an etching of a woman looking down at her abdomen. She has a colostomy and in her lap are rags and moss to absorb the output of the stoma. Then, in 1776, there is a record of a French physician constructing a stoma due to intestinal blockage. A sponge held tightly to the abdomen by an elastic band absorbed the output. While stoma construction was rare at this time, there are other reports of stoma formations, and of stoma output being managed through a variety of mechanisms such as leather pouches with drawstrings. Along with regular stoma enemas, these are the first records of attempts at creating ostomy appliances.

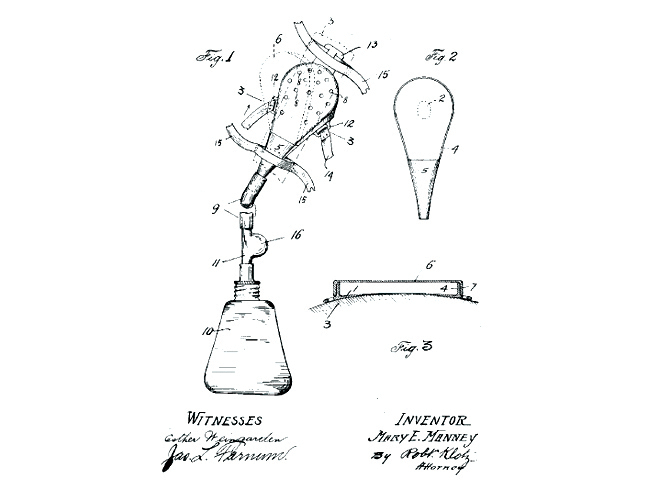

In 1912, Mary Manney, of Chicago, Illinois, filed a patent (granted in 1913) for a “surgical appliance, which may be secured to the body of a person upon whom a surgical operation has been performed; the device being particularly useful in operations of that character in which an incision has been made in the abdominal wall of the patient”. See Figure 1. In the 1920s, Dr. Alfred Strauss, a Chicago physician, came up with the idea of a rubber pouch that could be held in place on the abdomen by adhesives and belts.

Numerous other ostomy appliance patents were to be filed in the coming decades.

In the 1950s, innovation in products, patient care and surgical techniques evolved. This decade would provide the roots for a new healthcare profession; that of the Enterostomal Therapist, created by a tenacious ostomate from Ohio by the name of Norma Gill. At the same time, developments in surgical techniques were being explored at the Cleveland Clinic by Dr. Rupert Turnbull and Dr. George Crile, and plastics began to make their way into the manufacturing process. However, many of the manufacturers of ostomy appliances continued to use heavy rubber pouches and rubber or plastic face plates developed in the previous decades.

By the 1960s, there were approximately 25 manufacturers of ostomy products in the U.S. The ’60s saw progressive manufacturers of ostomy appliances turning away from bulky rubber bags to more aesthetic plastic films. This decade introduced Karaya, a major discovery in ostomy care. Karaya, originally a denture adhesive, is a vegetable gum produced as an exudate from trees of the genus Sterculia. As the story goes, Dr. Rupert Turnbull, while cleaning out a colleague’s lab, accidentally spilled some Karaya denture powder on his wet hands. He noticed that the Karaya had the ability to swell and cling to his wet skin and linked this to the needs of his ileostomy patients. In the 1960s, Karaya became the standard of use as a skin adhesive and protective barrier until the introduction of synthetic hydrocolloid barriers.

In the early ’70s the ostomy industry began to explore the needs of the ostomate. The philosophy changed from “we can provide what you need” to “what do you need that we can provide?” Developers recognized that a pouching system must be more than safe and effective; it must also consider quality of life.

The pouching system we know today is a disposable product made of a skin-friendly, water-repellent, cloth-like material covering film laminates. Qualities include pouch films that help mask odor; noise-reducing pouch material; filters to help reduce ballooning of the pouch due to gas; flexible and thin skin barriers that are designed to stick to the skin with or without the use of belts; and integrated closures eliminating the need for separate clamps. All this is contained within a system that may weigh between 12 and 20 grams. Modern systems are low in profile, and designed for comfort, confidence and discretion; with a goal to get people with ostomies back into everyday life. And the rest is history.